A rapid ongoing surge in corruption, looting, and organized crime perpetrated by Libya’s current rulers threatens the survival of the country’s essential institutions, including the nation’s vital oil sector. Unless bolder international policies are adopted, a relapse into armed conflict is a distinct possibility.

Read the full report and recommendations

Read the full report and recommendations

قرأ التقرير باللغة العربية

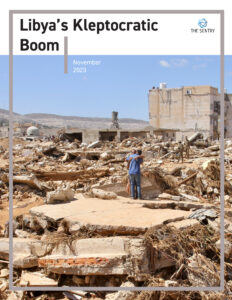

With foreign exchange reserves, vast natural resources, and a population of around seven million, Libya has remarkable per capita wealth. Yet, despite government expenditures continuing to rise, that wealth is not being sufficiently deployed in service to its population., The devastating loss of life and property from the September 2023 floods in Derna and other northeastern Libyan areas only confirms the current Libyan leaders’ neglect of significant portions of their nation’s economy and their indifference to crumbling infrastructure. In 2022, the United Nations (UN) assessed that 24% of women and 30% of children in Libya required targeted humanitarian assistance, and Libya ranks 171 out of 180 on the Transparency International

Global Corruption Perception Index. The frailty, opacity, and excessive personalization of state institutions provide Libya’s political entrepreneurs, armed group leaders, and organized crime bosses with numerous ways to steal or misuse public resources. Lately, the growth in Libya’s kleptocratic sector has accelerated.

This means that Libya is not heading for any new equilibrium or new order. Instead, there is a substantial risk that its current leaders might end up destroying the country’s most essential institutions, including the National Oil Corporation (NOC), which is responsible for almost all of the nation’s income.

Consequently, while policymakers in Washington and other Western capitals see the absence of large-scale exchange of fire since June 2020 as a sign of progress, they are underestimating the costs associated with turning a blind eye to the corruption of Libya’s current leadership—a small yet fractious set of mostly unelected individuals. Owing to the severity of the Libyan crisis’s most violent phases between 2014 and 2020, Washington and other Western capitals remain wary of a relapse into armed confrontation., Policymakers have therefore tended to focus their engagement on de-escalation and conflict mediation. In doing so, they have been tempted to look favorably at efforts by Libya’s incumbent elite to work out informal arrangements among themselves, the hope being that such tentative deals will result in stability and peace.

Kleptocracy, however, cannot be the basis upon which a functioning state is built: a corrupt bargain among Libya’s incumbent leaders does not constitute sustainable peacebuilding, especially given that no progress is currently being made in security sector reform or militia disarmament., Although no compelling analogy exists between Libya’s predicament and that of other troubled nations, lessons from Sudan, Iraq, Afghanistan, and Lebanon offer clear warnings of the dangers that Libya faces from its inability to disarm militias, combat kleptocracy, and provide for its citizens. The ongoing Sudan war, which erupted in April 2023, is partly attributable to the fact that both main warring factions were allowed to expand their kleptocratic empires in recent years. Lebanon’s economy has collapsed, while the leaders and technocrats who bankrupted it seek to evade responsibility. In oil-rich Iraq, the informal deals that buttress the nation’s current rulers fail to produce any positive outcomes: Amid weak governance, durable stability has remained elusive, armed groups’ supremacy has not receded, and the nation’s socioeconomic standards have continued to erode. In Afghanistan, the collapse of the Western-backed government in 2021 was partly attributable to the prevalence of corruption during the years leading up to Washington’s decision to withdraw and the subsequent takeover by the Taliban. High levels of corruption can significantly increase the likelihood of fresh outbreaks of conflict, casting doubt on the assumption that dividing the spoils can be a sustainable solution.

With regard to Libya, as long as the United States (US), United Kingdom (UK), and likeminded governments—as well as international organizations such as the UN and regional bodies such as the European Union (EU)—continue to pursue their current course, the state will remain captured by those who exploit it. Transactional bargains between existing power brokers with no popular mandate are so flimsy, opaque, and devoid of political legitimacy that they can yield neither a genuine reconciliation nor a sufficient improvement in outcomes for the population. The first reflex of the ruling elite is to maintain their own positions of power and secure their ability to extract wealth from the public domain. And as Libya’s kleptocratic activities swell, institutions grow weaker. New motives for violent clashes—different from those of the 2014-2020 era—develop.

While the contention among rival political authorities is well known, assessing Libya’s conflict through the lens of kleptocracy also highlights the need to understand the complexities of Libya’s banking sector and the growth of the black market. Libyan kleptocrats—who often enjoy the backing of foreign states—utilize Libya’s commercial banks and formal state institutions as conduits for recycling their ill-gotten funds domestically or for sending them abroad without facing meaningful scrutiny. The east-west split that has affected the country’s banking system since 2014 currently facilitates the maintenance of schemes for elite enrichment. Tackling these schemes in an even-handed fashion is rendered difficult by the lack of publicly available information, a problem often more pronounced in the country’s east than in the west. The institutional asymmetry that prevails between eastern and western Libya thus warps many policymakers’ perceptions of the nation’s illegal activities.

Policymakers seeking to avoid the danger of greater instability in Libya or the relapse into armed conflict should urgently address the country’s kleptocratic boom. Kleptocracy in Libya does not merely hurt the population, it also threatens neighboring countries and could impact Europe and the US. Thus, the priority must be to tackle the entrenched culture of impunity, an endeavor that should be pursued by bolstering checks and balances in Libya’s economic governance system and increasing the cost of profiteering from corruption and crime.